The cranial nerves are the nerves which come out straight from the brain, including the brainstem, in comparison to the spinal nerves, which come out from sections of the spinal cord. Of those, 10 out of 12 of these cranial nerves originate in the brainstem. Cranial nerves transfer information between the brain and parts of the human body, particularly to and from areas of the head and neck.

Spinal nerves exit from the spinal cord with the spinal nerve closest to the head (C1) exiting in the space above the first cervical vertebra. The cranial nerves, however, exit from the central nervous system above this region. Each cranial nerve is paired and is present on either side of the brain. Based on the definition in humans, there are twelve, sometimes thirteen, cranial nerve pairs, which have been assigned Roman numerals I-XII for identification, sometimes including cranial nerve zero as well. The numbering of the cranial nerves is based on the order in which they emerge from the brain, or from the front to the back of the brainstem.

The terminal nerves, olfactory nerves (I) and optic nerves (II) come out from the cerebrum, or forebrain, where the rest of the ten pairs of cranial nerves arise in the brainstem, which is the lower portion of the brain. The cranial nerves are considered components of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), though on a structural level, the olfactory, the optic and the trigeminal nerves are more accurately considered a portion of the central nervous system (CNS).

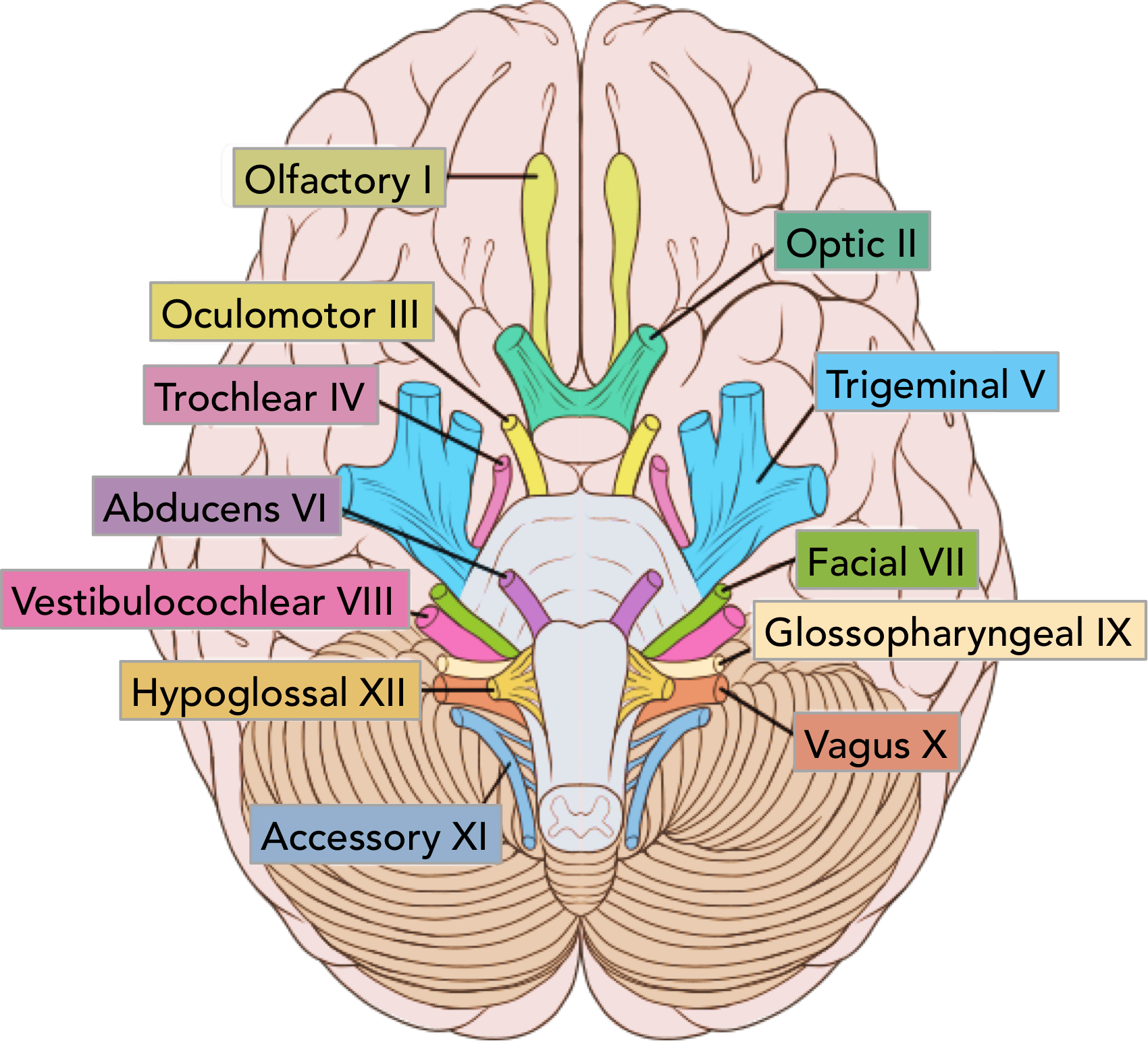

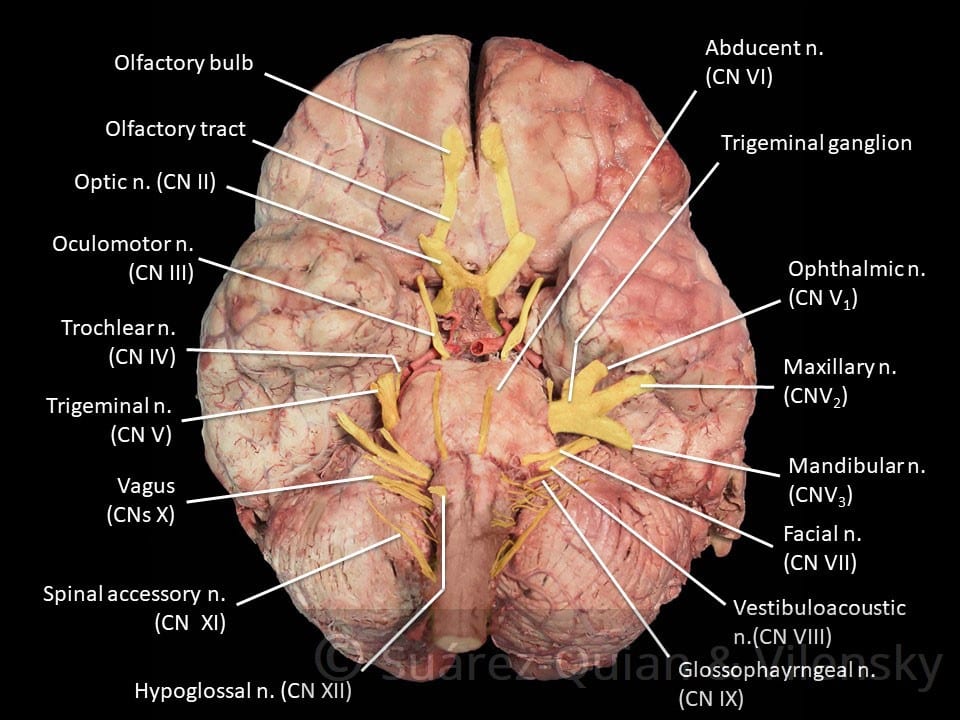

Most commonly, humans are believed to have twelve pairs of cranial nerves (I-XII). These include: the olfactory nerve (I), the optic nerve (II), the oculomotor nerve (III), the trochlear nerve (IV), the trigeminal nerve (V), the abducens nerve (VI), the facial nerve (VII), the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII), the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), the vagus nerve (X), the accessory nerve (XI), and the hypoglossal nerve (XII). There may be a thirteenth cranial nerve, known as the terminal nerve, or nerve N or O, which Is quite small and may or may not be functional in humans.

Anatomy of the Cranial Nerves

The cranial nerves are usually named according to their structure or function. For instance, the olfactory nerve (I) supplies smell, and the facial nerve (VII) supplies motor innervation to the face. Since Latin was the common language of the study of anatomy once the nerves were documented, recorded, and mentioned, many nerves maintain Greek or Latin names, including the trochlear nerve (IV), named based on its arrangement, as it supplies a muscle which attaches to a pulley (Greek: trochlea). The trigeminal nerve (V) is named based on its three components (Latin: trigeminus meaning triplets), and the vagus nerve (X) is known because of its wandering course (Latin: vagus).

In addition, cranial nerves are numbered according to their rostral-caudal, or front-back, position, when looking at the brain. If the brain is carefully removed from the skull, the nerves are typically visible in their numeric order, with the exception of the final nerve, the CN XII, which seems to come out from above, into the CN XI.

Cranial nerves have pathways within and away from the skull. The pathways inside the skull are known as “intracranial paths” and the pathways outside the skull are known as “extracranial pathways”. There are a number of holes in the skull known as “foramina”, by which the nerves may exit from the skull. All cranial nerves are paired, meaning that they can be found on both the left and right sides of the human body. The skin, muscles, or other structural function provided by a nerve on the same side of the human body as the side it originates from, is referred to as an ipsilateral function. In case the function is on the other hand from the origin of the nerve, then this is referred to as a contralateral function.

Location of the Cranial Nerves

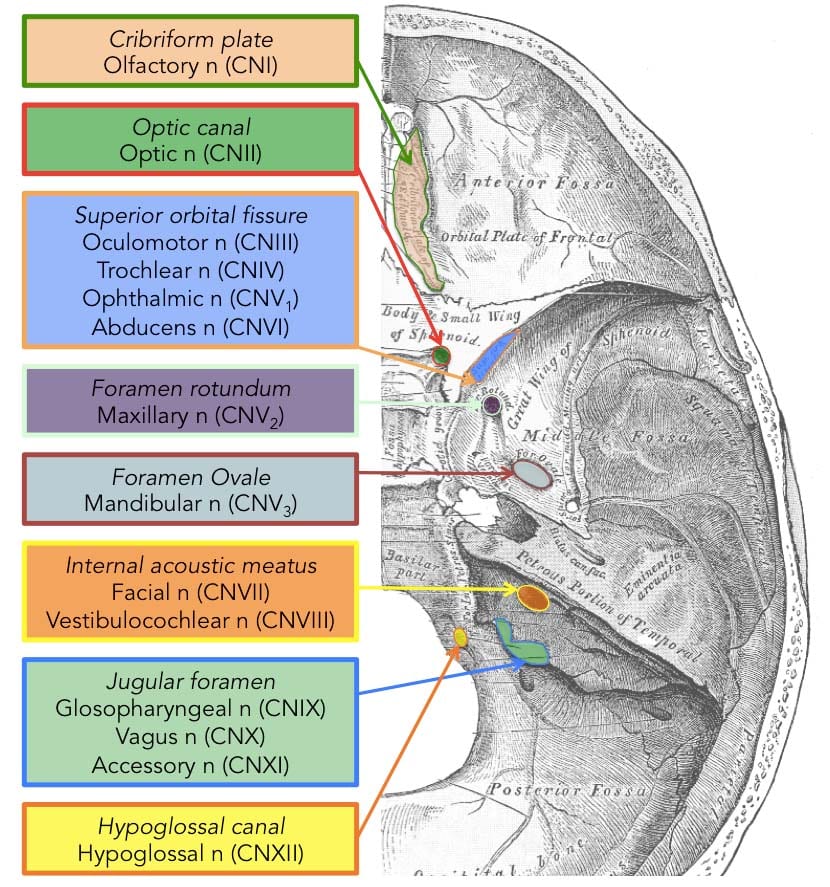

After coming out from the brain, the cranial nerves from inside the skull must leave this bony structure in order to arrive to their destinations. Several of the cranial nerves pass through the foramina, holes in the skull, as they journey to their destinations. Other nerves pass through bony canals, longer pathways enclosed by bone. The foramina and canals might contain more than just one cranial nerve, and may also include blood vessels. Below is a list of the twelve cranial nerves and a brief summary of their function.

- The olfactory nerve (I), composed of many small separate nerve fibers, which passes through perforations from the cribiform plate component of the ethmoid bone. These fibers end in the upper part of the nasal cavity and also operate to communicate impulses containing information about scents or odors into the brain.

- The optic nerve (II) passes through the optic foramen from the sphenoid bone in order to reach the eye. It communicates visual information to the brain.

- The oculomotor nerve (III), the trochlear nerve (IV), the abducens nerve (VI) and the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve (V1) journey through the cavernous sinus to the superior orbital fissure, passing out of the skull into the orbit. These cranial nerves control the tiny muscles that move the eye and also offer sensory innervation to the eye and orbit.

- The maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (V2) moves through the foramen rotundum from the sphenoid bone to supply the skin of the middle of the face.

- The mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V3) moves through the foramen ovale of the sphenoid bone to supply the lower face with sensory innervation. This nerve also extends to nearly all the muscles that control chewing.

- The facial nerve (VII) and the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII) both input the inner auditory canal in the temporal bone. The facial nerve subsequently extends to the side of the face using the stylomastoid foramen, also from the temporal bone. Its fibers then distribute to control and reach all of the muscles in charge of facial expressions. The vestibulocochlear nerve reaches the organs which control equilibrium and hearing in the temporal bone, and therefore doesn’t reach the outside surface of the skull.

- The glossopharyngeal (IX), the vagus nerve (X) and the accessory nerve (XI) all emerge from the skull via the jugular foramen to enter the neck. The glossopharyngeal nerve provides innervation to the upper throat and the back of the tongue, the vagus nerve offers innervation to the muscles at the voicebox, and proceeds down to provide parasympathetic innervation to the chest and abdomen. The accessory nerve controls the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles at the neck and shoulder.

- The hypoglossal nerve (XII) exits the skull using the hypoglossal canal at the occipital bone and also reaches the tongue to control virtually all the muscles involved in movements of this organ.

Function of the Cranial Nerves

The cranial nerves give motor and sensory innervation particularly to the structures found inside the neck and head. The sensory innervation contains both “overall” feelings, such as temperature and touch, and “particular” innervation, such as flavor, vision, smell, balance and hearing. For instance, the vagus nerve (X) gives sensory and autonomic, or parasympathetic, motor innervation to structures in the neck and to many of the organs in the chest and abdomen. Below, we will discuss the function of each cranial nerves in further detail.

Smell (I)

The olfactory nerve (I) communicates the sense of smell. Damage to the olfactory nerve (I) may cause an inability to smell, referred to as anosmia, a distortion in the sense of odor, referred to as parosmia, or even a distortion or absence of flavor. When there’s suspicion of a change in the sense of smell, every nostril is tested with compounds of known odors, such as coffee or soap. Intensely smelling chemicals, such as ammonia, can lead to the activation of pain receptors, known as nociceptors, of the trigeminal nerve which are situated in the nasal cavity, which may ultimately confound olfactory testing.

Vision (II)

The optic nerve (II) communicates visual information. Damage to the optic nerve (II) affects specific aspects of vision which are based on the area of the lesion. An individual may not be able to observe objects in their left or right sides, known as homonymous hemianopsia, or might have difficulty seeing objects on their outer visual areas, known as bitemporal hemianopsia, if the optic chiasm is included. Vision may be analyzed by examining the visual field, or simply by analyzing the retina with an ophthalmoscope, with a procedure called funduscopy. Visual field testing can be employed to pin-point structural lesions in the optic nerve, or further along the visual pathways.

Eye Movement (III, IV, VI)

The oculomotor nerve (III), the trochlear nerve (IV) and the abducens nerve (VI) coordinate eye motion. Damage to nerves III, IV, or VI can impact the movement of the eyeball globe. One or both eyes may be influenced; in either case, double vision, referred to as diplopia, will likely occur since the movements of the eyes are no longer synchronized. Nerves III, IV and VI are tested by observing the way the eye follows an object in different directions. This object may be a finger or even a pin, and may be moved at several directions to test for pursuit velocity. If the eyes don’t work together, the most likely cause is harm to a specific cranial nerve or its nuclei.

Damage to the oculomotor nerve (III) can lead to double vision, or diplopia, and inability to coordinate the movements of both eyes, known as strabismus, as well as eyelid drooping, referred to as ptosis, and pupil dilation, or mydriasis. Lesions may also lead to theinability to open the eye due to paralysis of the levator palpebrae muscle. People suffering from a lesion in the oculomotor nerve may compensate by leaning their heads to relieve symptoms because of paralysis of one or more of the eye muscles it regulates.

Damage to the trochlear nerve (IV) may also cause diplopia with all the eye adducted and raised. The result will be an eye which can’t move downwards properly, especially downwards when within an inward position. This is a result of impairment from the superior oblique muscle, which is innervated by the trochlear nerve.

Damage to the abducens nerve (VI) can also result in diplopia This is a result of impairment in the lateral rectus muscle, which is innervated by the abducens nerve.

Trigeminal nerve (V)

The trigeminal nerve (V) is made up of three different parts: The ophthalmic (V1), the maxillary (V2), as well as the Mandibular (V3) nerves. When put together, these nerves provide sensation to the skin of the face and also controls the muscles of mastication, or chewing. Conditions affecting the trigeminal nerve (V) include, trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headaches, and trigeminal zoster. Trigeminal neuralgia may occur later in life, from middle age onwards, most often after the age of 60, and it is a condition commonly associated with a very strong pain that spreads over the region innervated by the maxillary or mandibular nerve divisions of the trigeminal nerve (V2 and V3).

Facial expression (VII)

Lesions of the facial nerve (VII) may manifest as facial palsy. This is where a individual is unable to move the muscles on one or both sides of the face. An extremely frequent and generally temporary facial palsy is called Bell’s palsy. Bell’s Palsy is the end result of an idiopathic (unknown cause), unilateral lower motor neuron lesion of the facial nerve and is characterized by an inability to move the ipsilateral muscles of facial expression, including altitude of the eyebrow and furrowing of their forehead. Patients with Bell’s palsy frequently have a drooping mouth over the affected side and often have difficulty chewing since the buccinator muscle is affected. Bell’s palsy occurs very rarely, affecting around 40,000 Americans annually. Facial paralysis may be caused by other conditions including, stroke. Related conditions to Bell’s Palsy are sometimes misdiagnosed as Bell’s Palsy. Bell’s Palsy is a temporary condition usually lasting 2-6 months, but can have life-changing results and may reoccur often. Strokes typically also impact the cranial nerve by cutting off blood flow to nerves within the brain which is a clear indication that the nerve is present with similar symptoms.

Hearing and Equilibrium (VIII)

The vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII) divides into the vestibular and cochlear nerve. The vestibular region is in charge of innervating the vestibules and semicircular canal of the inner ear; this structure communicates information regarding equilibrium, and is a significant element of the vestibuloocular reflex, which keeps the brain stable and allows the eyes to track moving objects. The cochlear nerve communicates data from the cochlea, allowing sound to be heard. If damaged, the vestibular nerve can manifest the sensation of spinning and dizziness. Function of the vestibular nerve may be analyzed by placing warm and cold water in the ears and watching eye motions caloric stimulation. Damage to the vestibulocochlear nerve may also pose as repetitive and involuntary eye movements, previously described as nystagmus, particularly when looking in a horizontal plane. Damage to the cochlear nerve may cause partial or complete deafness in the affected ear.

Oral Sensation, Taste, and Salivation (IX)

The glossopharyngeal nerve (IX) innervates the stylopharyngeus muscle and supplies sensory innervation to the oropharynx and back of the tongue. The glossopharyngeal nerve additionally supplies parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland. Unilateral absence of a gag reflex suggests a lesion of the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and perhaps the vagus nerve (X).

Vagus Nerve (X)

Reduction of function of the vagus nerve (X) can lead to a reduction of parasympathetic innervation to quite a high number of structures. Important consequences of damage to the vagus nerve could include an increase in blood pressure and heart rate. Isolated dysfunction of just the vagus nerve is rare, but can be diagnosed with a hoarse voice, because of dysfunction of one of its branches, the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Damage to this nerve may result in difficulties swallowing.

Shoulder Elevation and Head-Turning (XI)

Damage to the accessory nerve (XI) can lead to ipsilateral weakness in the trapezius muscle. This can be tested by asking the patient to elevate their shoulders or shrug, where the shoulder blade, or scapula, will protrude to a winged position. Additionally, if the nerve is damaged, weakness or an inability to elevate the scapula may be present because the levator scapulae muscle is only able to provide this function. Based on the location of the lesion, there may also be weakness within the sternocleidomastoid muscle, which then acts to reverse the head so that the face points to the other side.

Tongue Movement (XII)

The hypoglossal nerve (XII) is unique in that it is innervated in the motor cortices of both hemispheres of the brain. Damage to the nerve at lower motor neuron level may cause fasciculations or atrophy of the muscles of the tongue. The fasciculations of the tongue are sometimes said to look like a”bag of worms”. Upper motor neuron damage won’t cause atrophy or fasciculations, but only weakness of the innervated muscles. Once the nerve is damaged, it will lead to weakness of tongue movement on one side. When damaged and extended, the tongue will move towards the weaker or damaged side, as shown in the image.

Dr. Alex Jimenez’s Insights

The cranial nerves are a set of 12 nerves which emerge directly from the brain. The first two nerves, known as the olfactory nerve and the optic nerve, come out from the cerebellum, where the remaining ten cranial nerves emerge from the brain stem. The names of the cranial nerves relate directly to their function and they are also numerically identified in roman numerals I-XII by their specific location of the brain and by the order in which they exit the cranium. Damage to any of the above mentioned cranial nerves can cause health issues associated to the specific structure and function of each nerve. Common signs and symptoms in these regions can help healthcare professionals identify the affected cranial nerves.

The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Additional Topics: Sciatica

Sciatica is medically referred to as a collection of symptoms, rather than a single injury and/or condition. Symptoms of sciatic nerve pain, or sciatica, can vary in frequency and intensity, however, it is most commonly described as a sudden, sharp (knife-like) or electrical pain that radiates from the low back down the buttocks, hips, thighs and legs into the foot. Other symptoms of sciatica may include, tingling or burning sensations, numbness and weakness along the length of the sciatic nerve. Sciatica most frequently affects individuals between the ages of 30 and 50 years. It may often develop as a result of the degeneration of the spine due to age, however, the compression and irritation of the sciatic nerve caused by a bulging or herniated disc, among other spinal health issues, may also cause sciatic nerve pain.

EXTRA IMPORTANT TOPIC: Sciatica Rehabilitation, Causes and Symptoms

MORE TOPICS: EXTRA EXTRA: Back Pain | El Paso, Texas

Post Disclaimer *

Professional Scope of Practice *

The information herein on "Structure and Function of the Cranial Nerves in El Paso, TX" is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional or licensed physician and is not medical advice. We encourage you to make healthcare decisions based on your research and partnership with a qualified healthcare professional.

Blog Information & Scope Discussions

Welcome to El Paso's Premier Fitness, Injury Care Clinic & Wellness Blog, where Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, FNP-C, a Multi-State board-certified Family Practice Nurse Practitioner (FNP-BC) and Chiropractor (DC), presents insights on how our multidisciplinary team is dedicated to holistic healing and personalized care. Our practice aligns with evidence-based treatment protocols inspired by integrative medicine principles, similar to those found on this site and our family practice-based chiromed.com site, focusing on restoring health naturally for patients of all ages.

Our areas of multidisciplinary practice include Wellness & Nutrition, Chronic Pain, Personal Injury, Auto Accident Care, Work Injuries, Back Injury, Low Back Pain, Neck Pain, Migraine Headaches, Sports Injuries, Severe Sciatica, Scoliosis, Complex Herniated Discs, Fibromyalgia, Chronic Pain, Complex Injuries, Stress Management, Functional Medicine Treatments, and in-scope care protocols.

Our information scope is multidisciplinary, focusing on musculoskeletal and physical medicine, wellness, contributing etiological viscerosomatic disturbances within clinical presentations, associated somato-visceral reflex clinical dynamics, subluxation complexes, sensitive health issues, and functional medicine articles, topics, and discussions.

We provide and present clinical collaboration with specialists from various disciplines. Each specialist is governed by their professional scope of practice and their jurisdiction of licensure. We use functional health & wellness protocols to treat and support care for musculoskeletal injuries or disorders.

Our videos, posts, topics, and insights address clinical matters and issues that are directly or indirectly related to our clinical scope of practice.

Our office has made a reasonable effort to provide supportive citations and has identified relevant research studies that support our posts. We provide copies of supporting research studies upon request to regulatory boards and the public.

We understand that we cover matters that require an additional explanation of how they may assist in a particular care plan or treatment protocol; therefore, to discuss the subject matter above further, please feel free to ask Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC, or contact us at 915-850-0900.

We are here to help you and your family.

Blessings

Dr. Alex Jimenez DC, MSACP, APRN, FNP-BC*, CCST, IFMCP, CFMP, ATN

email: [email protected]

Multidisciplinary Licensing & Board Certifications:

Licensed as a Doctor of Chiropractic (DC) in Texas & New Mexico*

Texas DC License #: TX5807, Verified: TX5807

New Mexico DC License #: NM-DC2182, Verified: NM-DC2182

Multi-State Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN*) in Texas & Multi-States

Multistate Compact APRN License by Endorsement (42 States)

Texas APRN License #: 1191402, Verified: 1191402 *

Florida APRN License #: 11043890, Verified: APRN11043890 *

Verify Link: Nursys License Verifier

* Prescriptive Authority Authorized

ANCC FNP-BC: Board Certified Nurse Practitioner*

Compact Status: Multi-State License: Authorized to Practice in 40 States*

Graduate with Honors: ICHS: MSN-FNP (Family Nurse Practitioner Program)

Degree Granted. Master's in Family Practice MSN Diploma (Cum Laude)

Dr. Alex Jimenez, DC, APRN, FNP-BC*, CFMP, IFMCP, ATN, CCST

My Digital Business Card

RN: Registered Nurse

APRNP: Advanced Practice Registered Nurse

FNP: Family Practice Specialization

DC: Doctor of Chiropractic

CFMP: Certified Functional Medicine Provider

MSN-FNP: Master of Science in Family Practice Medicine

MSACP: Master of Science in Advanced Clinical Practice

IFMCP: Institute of Functional Medicine

CCST: Certified Chiropractic Spinal Trauma

ATN: Advanced Translational Neutrogenomics